Volatility Term Structure

American options are highly sensitive to the path of the underlying asset because they can be early exercised. Small mistakes in volatility assumptions can lead to significant pricing errors.

Why Volatility Term Structure Matters

Imagine pricing an American call option on a stock that will pay a cash dividend and has a major earnings announcement scheduled before expiration. Earnings events create sharp, localized spikes in volatility: volatility rises steeply around the announcement window and remains near normal levels before and after. This produces a highly non-flat volatility term structure.

A basic pricer that uses only a single “term volatility” — effectively assuming volatility is constant over the entire life of the option — cannot capture this event-distorted volatility term structure. By ignoring how volatility behaves before, during, and after the event, such a model can introduce substantial mispricing.

To see how this mispricing arises, consider where the true volatility actually occurs. Suppose the stock goes ex-dividend before the earnings announcement. Most of the volatility spike occurs after the dividend date, meaning a large portion of the option’s time value lies in this high-volatility region. A call holder would need to forfeit substantial remaining time value in order to collect the dividend, making early exercise less attractive than it would be under flat volatility.

But a flat-vol model spreads the earnings volatility spike evenly across the entire option life, making the post-dividend period appear calmer than it really is. It incorrectly assumes the holder gives up less time value to capture the dividend. This leads the model to overprice the early exercise premium and thus overprice the call option itself.

Now consider the opposite ordering: the stock goes ex-dividend after the earnings announcement. In reality, most of the volatility spike has already passed. The period following the ex-dividend date is relatively quiet, making early exercise more attractive — the call holder sacrifices little remaining time value to collect the dividend.

A flat-vol pricer again gets this wrong. By smearing part of the event spike into the post-dividend period, it makes the remaining time value appear higher than it truly is. The model incorrectly believes the holder is giving up more time value than they actually would. As a result, it underprices the early exercise premium and therefore underprices the call option.

In both scenarios, the interaction between event-driven volatility and dividend timing is crucial. A model that treats volatility as uniform through time cannot replicate the true variance profile of the underlying across different segments of the option’s life.

A Real-World Example

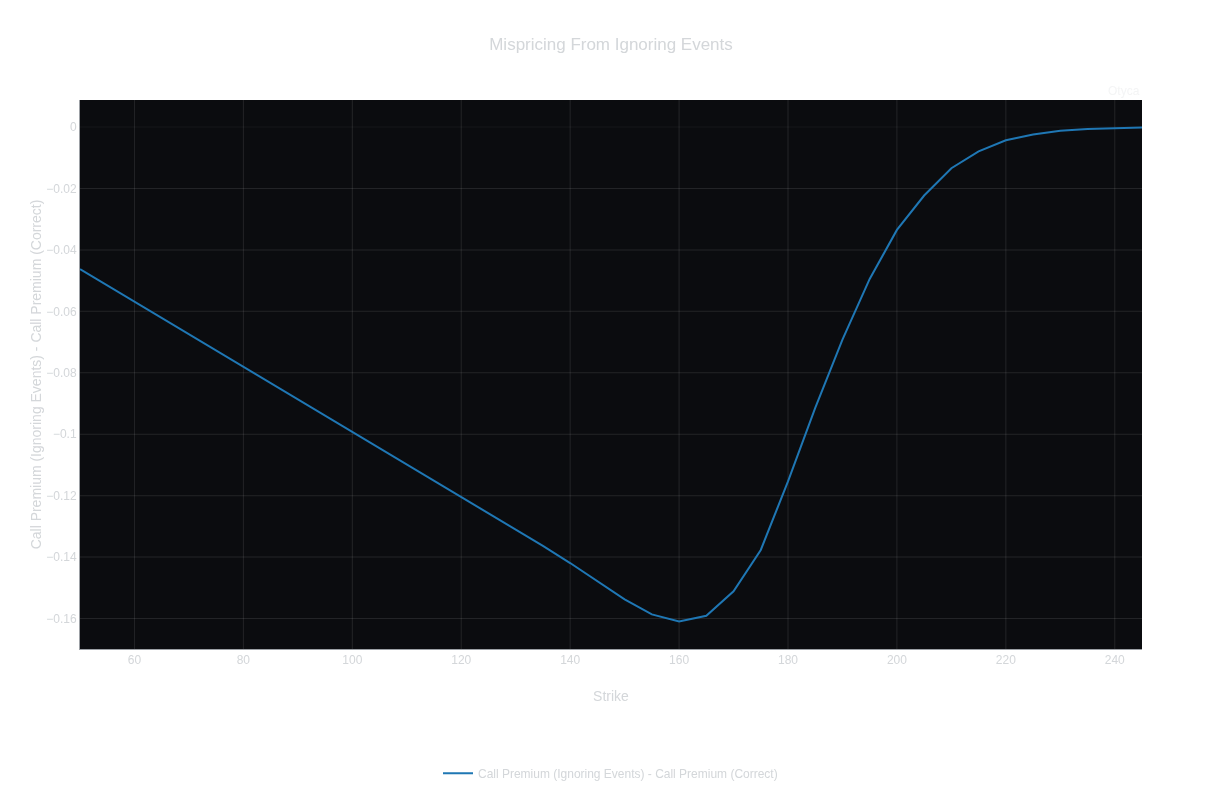

The figure below shows how severely a flat-volatility pricer can misprice options when major events distort the term structure. On January 19th, 2024, AAPL call options expiring on February 16th were impacted by an upcoming earnings announcement on February 1st and a $0.24 dividend with an ex-dividend date of February 9th. A simple pricer that ignores these dynamics mispriced certain strikes by as much as $0.16 — while the typical bid–ask spread for these calls in this expiry can be as small as $0.04. In other words, the model error was 4x the market spread.

How Much Does It Really Matter?

Our American option pricer models the full volatility term structure—capturing earnings-driven volatility spikes, dividend timing effects, and the interaction between them—to deliver event-aware, path-consistent valuations. Experience the difference directly with our option calculator here.